August Alexander Klengel – Piano and Chamber Music CD

Who wants to support our project on Kickstater? We (Trio Klengel) would like to reach our fundraising goal and make this recording happen!

About the composer:

The name of the German composer August Alexander Klengel (1783-1852) is mentioned nowadays only in relation with his two volumes of works,“Canons and Fugues,” which were written during the last 25 years of his life.

Everything else from his creative work is either forgotten or completely ignored and unknown.

However, his music deserves our attention as in his early works Klengel clearly shines as an early romantic composer, undoubtedly being an inspiration for many of his young fellow composers at the time (Mendelssohn and Chopin, just to name a few).

The compositions’ titles are hinting their content: Romances, Nocturnes… Surprisingly, no one has yet looked seriously into his scores and so this will be the first recording that will attempt to do so.

The following works by Klengel will be included in this CD:

Romance (op.6) – for Piano

Nocturne No.5 (op. 23) – for Piano

Fantaisie sur un thème russe (op.25 ) – for Piano

Trois romances (op. 34) – for Piano

Air suisse avec variations (op.32) – for Violin and Piano

Trio (op. 36) for Violin, Cello and Piano

We are very grateful to Toccata Classics who has chosen to release our recording.

We would like to thank the Museum Behnhaus Drägerhaus Lübeck for the kind permission to use the portrait of A. A. Klengel by Vogel von Vogelstein.

Thanks to all who understand the hard work and dedication that we put into this project. We will not be able to do this alone, so we truly rely on you.

DANIEL STEIBELT – ONCE MORE

"This composer (Steibelt) is a young man, with a great hand on his instrument and possessed of knowledge and real Genius"

Charles Burney – Letter (1797)

"Last week, Mr. Steibelt, the only great genius of his kind and a foolish fellow, gave a brilliant concert. His beautiful performance was beyond description, I had never heard such a thing before, and he demonstrates subtle taste, humour and spirit, combined with his great skill".

Johann Gottlieb Naumann – Letter (1800)

Steibelt - what a talent! What power of execution! Liszt and Steibelt are the two men whose interpretation on the piano affected me. Steibelt was the first to reveal the romantic music...

Laure d’Abrantès – Memoirs (1832)

If we are to sum up Steibelt’s 2015 Jubilee Year, the result will so far not be satisfying. From all the forgotten composers, Daniel Steibelt is still the most underrated. The stupid comments and assertions all over the net make me play with the idea of creating an “Honour’s Preservation Society” for Steibelt and all the lesser-known composers who are so easily abased. A sentence like the following one could in this case already be a subject for a lawsuit:

Perhaps the finest example of Beethoven’s skill though was the time he was challenged to a piano duel (yes those happened) by noted asshat, Daniel Steibelt. Steibelt was known in popular circles as the "unvirtuous virtuoso" for his habit of being a lying, cheating ass who badmouthed everyone who played better than him (pretty much everyone). According to all known sources, Beethoven utterly trounced Steibelt in the first two rounds, at first by playing a Mozart piece, and secondly by improvising harder than Steibelt could.

A certain Karl Smallwood, who imagines being a head writer and researcher, invented this balderdash. I am sure there is no need to say that a simple decency is a question of primary education.

Do not think that only English speaking people are subject to this kind of nonsense:

Kreulnarrates about some in the 19th century very common keyboard duels between virtuosos. Like the one between Ludwig van Beethoven and Daniel Steibelt. Beethoven won by improvising all day long on a Cello Suite by Steibelt.

Kreul erzählt dann von den im 19. Jahrhundert üblichen Tastenduellen zwischen den Virtuosen am Klavier. Etwa von dem zwischen Ludwig van Beethoven und Daniel Steibelt. Beethoven gewann, indem er den ganzen Tag lang über eine Cellosuite von Steibelt improvisierte.

DID Beethoven really?? All day long?

Now forget these samples of small fry. Much more revealing is the preconceived attitude of those who are professionally writing about Steibelt. Of course, no one can like a composer or his music by force. Yet the expert has to be above his personal preferences, he has to stay professional.

Because of my deep interest in the still not well-known period covering the end of the 18th, and the beginning of the 19th century, I always expect the same openness and enthusiasm toward the subject from the other colleagues and musicologists, or even more, some knowledge of the facts. That is why after reading some reviews of a CD of Steibelt’s 3 concertos by Howard Shelley for Hyperion and the booklet by Richard Wigmore I had to give way to my comments (at least to some of them).

Unfortunately, I was not able to understand and admire Wigmore’s splendid notes (a mixture of erudition and quiet wit) as pointed by the reviewer Harriet Smith for Gramophone reviews.

Instead of using such a recording of concertos by a forgotten composer as a great occasion for giving new, interesting facts, the banally repeated story about Beethoven and Steibelt’s duel alternates in the booklet with some superficial biographical information and also quite a banal overview of the concertos. Despite Mr. Wigmore’s promised erudition, we have no access to real information, only to always the same old outworn quotations. An example:

While in London Steibelt married an English pianist who was also a dab hand on the tambourine prompting him to add tambourine parts to many of his later works, not least the ‘Grand concerto militaire’.

Many of his later works? Daniel Steibelt left over 150 piano works, among them only four or five are for tambourine and piano.

Now let me reassure you that the use of the tambourine in the Grand concerto militaire No.7 has NOTHING to do with Steibelt’s wife and her playing the tambourine. In the Seventh concerto there are two orchestras; one of them is a military band (that gives the name to the concerto). Since the 17th century, the military bands in Europe had used triangles, cymbals, bass drums, tambourines, crescents carillons, chimes (Glockenspiel). (A much later example could be Gustave Holst’s First Suite in E-flat for a military band where the tambourine is used as well.)

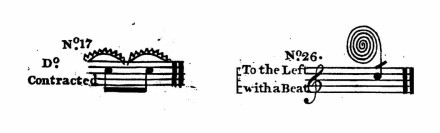

The wife in question was Catherine Dale (1778-1825), the daughter of Joseph Dale (1750-1828), a well-known English composer and publisher. Already at a very young age, Catherine was a virtuoso on the tambourine and played the piano quite well, too. Her interest in the instrument was not a hazardous one; Joseph Dale himself was very fond of it and had a few patents for perfecting the tambourine, composed sonatas for the tambourine and the pianoforte and actually invented a special tambourine notation, now completely forgotten:

Today he is mentioned in many treatises of the history of percussions. Certainly, Daniel Steibelt was strongly influenced by his father-in-law, as were his fellow composers Muzio Clementi and J.B. Cramer who wrote for the same ensemble as well. From my own experience, I can say that Steibelt’s pieces for the duo are very pleasant to play; they are probably one of the first works for piano and percussion. Only much later, in the 20th century, composers like Béla Bartók or the Brazilian Osvaldo Lacerda (1927-2011) will use such a combination. So this is, in fact, an interesting detail from the English music history of the 19th century.

I puzzled over many assertions in the booklet like for example:

In 1808 Steibelt abruptly left Paris to take up an appointment as director of the French Opera in St Petersburg, his departure precipitated by the need to escape his creditors.

Mr.Wigmore’s word “abruptly” means at least half a year (well, they were veeery slow then). Because half a year or more before leaving Paris, Steibelt published different piano pieces, some dedicated to the Russian queen and among them “Départ de Paris pour Saint Pétersbourg” – probably just in case his creditors thought he might escape? For all who are interested to have an exact information about Steibelt, there is an article by Olivier Feignier.

Where Harriet Smith enjoys an erudite remark, I find a lack of knowledge of the period:

As a natural showman, Steibelt seemed to lack confidence writing and playing slow, sustained music. Many of his Andantes and Adagios use pre-existing melodies; and like the slow movement of the fifth concerto, the Adagio non troppo of No 3 taps into the vogue for Scottish folk tunes, gently sentimentalized for polite society.

Quite fascinating – although Steibelt lacked confidence in writing and playing slow, sustained music, he nevertheless wrote many Andantes and Adagios and then had to play them too, probably without confidence?.. poor Steibelt… It would be interesting to know which of them use pre-existing melodies, but that will remain Mr. Wigmore’s secret, as well as his knowledge of Steibelt’s music as a whole. Now we come to another particular fact in English musical history. The interest for the Scottish and Irish folk tunes was much more than a simple vogue. The Scots and the Irish were the first in Europe to be interested in folk songs, beginning to collect and to publish them already in the first decades of the 18th century. A very English institute, The Catch and Glee clubs (where people enjoyed singing songs in a small group) – existed over for two hundred years. The song dominated the musical life of the society, especially at the beginning of the 19th century. Later it extended to such a degree that “publishers were trying to popularize the sonata by commissioning ones in which the latter movements, or even all the movements, were based on popular tunes” (Nicholas Temperley in “The Romantic Age 1800-1914”). Every respected composer, English or a foreigner in England, owed it to themselves to compose variations on a Scottish or Irish folk song (surprisingly a similar situation with the folk songs existed in Russia).

Just two examples: Beethoven himself arranged some Irish songs for George Thomson in Edinburgh and used many tunes for his variations – probably gently sentimentalized for the same polite society? Mendelssohn’s “The Last Rose in Summer” variations op.15 on an Irish song of Thomas Moore is also a tribute to this tradition. Therefore, it was a well-founded and logical decision of Steibelt’s, to use a folk song in a work with program movements like “The Storm” or “A la chasse”. (Whatever Mr. Wigmore may think of it.)

I was unable to understand the “quiet wit” of the booklet’s author. May be the readers can help where I was helpless:

Around 1816, with Napoleon safely in exile on St Helena, Steibelt followed suit with his Piano Concerto No 7 in E minor, ‘Grand concerto militaire’.

Does it really mean that with Napoleon still in France, Steibelt would never ever have dared to write a concerto in E minor? Even more – a Military concerto in E minor? Steibelt himself knew nothing about such an expert insight in his life, and already on the 1st March 1811, happily played his newly composed Seventh concerto for the Russian audience and every year since continued to perform it in his concerts. Thus Wigmore’s claim:

Military dotted rhythms rule, though the underlying chromatic harmonies give the opening theme a faintly melancholy air (shades here of Hummel’s virtually contemporary A minor concerto, Op 85)– (written in 1816 A.P.-F.)

is absolutely out of place.

Harriet Smith’s review continues in the same tune. Lamenting the awful lot of notes that Howard Shelley had to learn, yet doubting whether that was time well spent is another matter. Echoing Wigmore:

The most convincing moments in these pieces are those that sound Mozartian, though it can’t be said that Steibelt is either a conjurer of memorable melodies or harmonically a deep thinker.......The slow movements of the Third and Fifth Concertos are both based on folk tunes, in the case of the latter a set of variations on ‘Ye banks and braes o’ bonnie Doon’; unfortunately all this does is show (?) the limitations of Steibelt’s imagination.

It is not surprising that with such an attitude (or limited imagination?) R. Wigmore as well as H. Smith and other reviewers are not able to notice nothing else. Already in Steibelt’s Third concerto (Ist movement) will the mere listener discover a language that does not sounds Mozartian but belongs to a new musical current:

[youtube]https://youtu.be/hReXuw0FrX8[/youtube]

Why not mention the interesting resemblance with the beginning of the Largo (IInd movement) of Beethoven’s First concerto, written at the same period:

The attentive listener will certainly also enjoy the early romantic elements in Steibelt’s Seventh concerto:

[youtube]https://youtu.be/alcixK7IkVY[/youtube]

The only sensible remark in Smith’s review is the following:

though there is an unexpected cut of some 70 bars after the pause – 5’22” into tr 8 – which seems an odd decision.

Indeed, an odd decision, and not at all mentioned in the booklet. Why?

In his book “The End of the Early Music”, Bruce Haynes outlines exactly the situation:

Composers became the heroes, promoted to the status of geniuses. Musical pantheons were erected, and plaster factories geared up to create busts of composers, like so many ancient Roman emperors, the resemblance to the actual composer a matter of chance. … And Canonism is selective; admission to the gold-like domain of great composers has been virtually impossible since about the time of the First World War. … The identity of the artist-composer is important to the Canonism because works by hero/genius composers are by definition imbued with “greatness” (regardless of their perceived musical qualities, or lack of them). And, like the star phenomenon in modern culture, a work takes on interest when it is associated with a big name, and becomes worthy of reconsideration…

Herewith a perfect example of the above-mentioned phenomenon:

The journalist Remy Franck, (editor-in-chief of the magazine Pizzicato and the author of another review) in his zeal to praise above all Beethoven arrives to revolutionary statement:

The third concert (of Steibelt, written in 1797/8 - A.P.-F.) begins with a flowing Allegro, afterwards the composer tries to captivate the listener with a soulfully prepared Scottish melody, and serves him in the 3rd movement a Pastorale with embedded Storm, ten years after Beethoven's Sixth Symphony.

Das 3. Konzert beginnt mit einem flüssigen Allegro, danach versucht der Komponist, den Hörer mit einer gefühlvoll aufbereiteten schottischen Melodie zu fesseln, und serviert ihm im 3. Satz eine Pastorale mit eingebettetem Sturm, gut zehn Jahre nach Beethovens Sechster Symphonie.

This would mean that Beethoven composed his Symphony No. 6, op. 68 in 1787, being 17 years old and not in 1808 as we had thought so far! Great news for Beethoven’s research.

Mr Frank also reveals us that:

Steibelt‘s concerts entirely aim at pianistic brilliance and effect, and Howard Shelley looks for nothing else in them.

Steibelts Konzerte sind ganz auf klavieristische Brillanz und Wirkung aus aus, und Howard Shelly sucht darin auch nicht mehr.

In my opinion, the entire aim of reviewers and critics is to copy each other without thinking or looking into facts.

Seriously, it is clear that despite the huge possibilities of the modern world, we are entering the dark age of negligence and indifference. Do not let yourself be misled; this concerns not only the unknown composers but the famous ones as well. Otherwise how would the following be possible:

The Continuing “Jeune homme” Nonsense

or

“The Young Franz Schubert”: An Ineradicable Misidentification?